Kirkcudbright & the de la Poles

AND DID THOSE FEET…

On the 21st of September 1523, a French fleet landed a small invasion force at Kirkcudbright on the South West coast of Scotland. Was Richard de la Pole, the last prince of the House of York to actively seek the English throne, with them?

Image: portrait of Francis I, King of France, by Jean Clouet.

The year 1523 was especially difficult for Francis I, King of France. His childhood friend and most trusted advisor, the Duke of Bourbon, had suddenly defected to Francis’ hated enemy, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, yet this crisis was largely of Francis’ making.

In an effort to secure more funds for his proposed invasion of Italy, Francis had tried to seize the vast estates that had belonged to Bourbon’s late wife, Suzanne. To do this, Francis had ordered the widowed duke to marry Louise of Savoy, who just happened to be the king's mother. Perhaps understandably, Bourbon had refused to wed a woman much older than himself but disobeying the king was most unwise so he decided to seek refuge in the Holy Roman Empire.

The Emperor was only too pleased to offer his support and together Charles and Bourbon hatched a plot to overthrow Francis. To add to the French king's’ woes, Charles and Bourbon brought England’s king, Henry VIII, into their alliance and under the terms of their secret treaty, they agreed to partition France between themselves.

In exchange for Anglo-imperial support for Bourbon’s bid for the throne, Charles would receive all the lands in eastern France that had been lost in successive wars fought by his grandfather, the Emperor Maximilian. Likewise, Henry would receive Gascony, Normandy and all the other lands in western France once ruled by England's kings. Bourbon would be left with the rump of the French kingdom in central and southern France.

Image: Portrait of Charles, Duke of Bourbon, by Jean Clouet

To achieve this, Charles and Bourbon planned to invade France through Flanders and link up with Henry's army, which would be assembled in Calais. Their united force would then march on Paris and force Francis to abdicate - but what has all this to do with Richard de la Pole, the last in a long line of Yorkist pretenders to England's throne?

The simple answer is that Francis intended to fight fire with fire. If Henry was backing a French rebel then he would help Richard topple the Tudors and restore the House of York. Yet this begs another question: who was Richard de la Pole and how valid was his claim to England’s ‘hollow crown'?

In fact, Richard’s blood was considerably more blue than that of his Tudor rival. He was the youngest son of John de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk and his wife, Elizabeth, who was the sister of the Yorkist kings Edward IV and Richard III.

As a consequence, Richard de la Pole could trace his royal ancestry from the second and fourth sons of Edward III, Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence and Edmund of Langley, Duke of York. By contrast, Henry VIII’s claim derived from his grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, who was descended from the illegitimate (later legitimised) children of Edward III’s third son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.

Back in 1484 the de la Pole claim gained considerable momentum after the death of Richard III's son, Edward of Middleham. Without an heir of his own, Richard III had decided that the eldest of his nephews, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, should succeed him.

Of course it was all in vain and, following Richard III’s death at the Battle of Bosworth, the de la Poles had to abandon their royal ambitions and accept the victorious Henry Tudor as King Henry VII. Typically, this fragile peace did not last long and less than two years after Bosworth, John de la Pole threw in his lot with the ill-starred Simnel rebellion.

Image - portrait of a 16th Century gentleman, possibly Richard de la Pole.

The de la Pole brothers’ first tilt at the throne ended in 1487, when John was killed at the Battle of Stoke Field. Following his death the Yorkist mantle passed to his younger brother, Edmund, and the pattern quickly repeated itself.

Despite an initial period of rapprochement with Henry VII, Edmund was soon forced into exile and he began plotting his own rebellion with the help of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian. Like his brother, John, Edmund’s schemes also ended in failure; in 1506, he was betrayed by his erstwhile imperial ally and sent back to England in chains. The second of the de la Pole rebels spent the last seven years of his life in the Tower of London and he was executed in 1513.

Though Richard had accompanied his brother into exile, he managed to escape Edmund’s fate by fleeing to Hungary. Yet he too was determined to restore the House of York and so, realising Maximilian could not be trusted, he sought the help of the French king, Louis XII, and his successor, Francis I.

In return for the promise of French aid, Richard agreed to fight for France as a mercenary and during the Navarrese War of 1512 he gained a reputation as a very capable captain. Sadly, Richard’s participation in this war, in which France tried to prevent an Anglo-Spanish army from conquering Navarre for Charles and recapturing Gascony for Henry, meant Edmund was executed in retaliation.

Undaunted by his brother’s death, Richard continued his quest for the English throne and his plan to land a French army in southern England, was due to take place in 1514. However, a sudden warming of relations between England and France ended Richard's usefulness as a political pawn. The 1514 invasion was cancelled and Richard was exiled to Metz, then a free city within the Holy Roman Empire. Though Louis died in 1515, Richard remained in the political wilderness for the next nine years.

Image: John Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany, by Jean Clouet

Finally, in 1523, the Bourbon rebellion gave Richard his chance. As mentioned above, Louis' successor, Francis, decided to weaken the triumvirate ranged against him by playing Henry VIII at his own game.

If Henry was backing Bourbon then Francis would support Richard but unlike Louis' plan to land an army in Devon or Dorset, Francis' scheme would transport a French army to southern Scotland and invade England from the north. Moreover, this would be done whilst the bulk of the English army was in Calais, preparing to invade France.

In this enterprise Francis and Richard had two vital allies. The first was John Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany, who, despite his name, was more French than Scottish. John’s father, Alexander Stewart, 1st Duke of Albany, had fled to France in 1479, after his own rebellion against his brother, the Scottish King James III, had failed.

Whilst in exile, Alexander had wed his cousin, the immensely wealthy French heiress, Anne de la Tour d’Auvergne, and their son, John, had been born in France in 1482. Interestingly, Alexander’s rebellion had been backed by Richard de la Pole’s uncles, the Yorkist king Edward IV and the future King Richard III, so John Stewart had a natural affinity with the House of York.

In 1513 John Stewart became Scotland’s heir presumptive after the death of James IV, at the Battle of Flodden, placed his infant son, James V, on the Scottish throne. More importantly, Albany soon gained the upper hand in the struggle to be the boy-king’s regent.

Image: Margaret Tudor, wife of James IV, mother of James V, sister of Henry VIII and the Duke of Albany's rival for the Scottish regency.

Opposing Albany in this fight for control of Scotland, was the young king’s mother, Margaret Tudor, who was Henry VIII’s sister. Unfortunately for Margaret, her English connections, combined with an ill-advised second marriage to the dissolute Earl of Angus, made her extremely unpopular north of the Border.

The Scottish nobles' deep distrust of Margaret persuaded them to offer the regency to Albany and the King of France was very keen to have a pro-French ruler in Edinburgh. Francis therefore gave Albany a small army and a fleet of 8 ships to enforce his rule and the new regent arrived in Scotland in the spring of 1515.

Though Albany's regency was by no means straightforward, once he had seized power, he was able to follow an aggressive pro-French foreign policy. Accordingly, when Francis asked his protégé to open a second front in the war against Charles, Henry and Bourbon, Albany was only too happy to oblige.

Image: the ruins of Askeaton Castle, Co. Limerick, seat of the Earls of Desmond.

The second of Albany and Richard’s allies in Francis’ scheme to invade northern England was the Irish noble James Fitzgerald,10th Earl of Desmond. His family also had longstanding connections to the House of York, thanks to their hereditary feud with the pro-Lancastrian/pro-Tudor earls of Ormond. James’ father, Maurice the Lame, had supported Perkin Warbeck’s bid for the throne and his Kildare cousins had backed the Simnel rebellion led by Richard’s brother, John.

The new plan to conquer England adopted a similar strategy used by the supporters of Simnel and Warbeck. Though the foreign mercenaries recruited by Albany, and led by Richard, would be French rather than German, they too would be joined by an Irish army under a Fitzgerald.

Likewise, Richard would follow in the footsteps of his brother, John, and land on England’s northwest frontier. However, unlike Warbeck's invasion of Northumberland in 1496, which had the backing of the Scottish king James IV, and despite Albany seizing Scotland, the Scots had scant interest in fighting a war in which they had little to gain.

Image: the ford over the Tweed where Albany planned to cross into England.

The Scottish reluctance to take part in the scheme to make the youngest of the de la Pole brothers King Richard IV is largely due to a fear of suffering another crushing defeat, as they had done at Flodden ten years earlier. That said, no Scot could pass up the chance to make trouble in England and the first part of Richard and Albany's plan went better than either man dared hope.

A clever campaign of disinformation had persuaded Henry to mothball the English fleet for the winter, so Richard and Albany's armada was able to sail up the Irish Sea undetected and land their expeditionary force unopposed. The French troops disembarked at Kirkcudbright, on the northern shore of the Solway Firth, on the 21st of September 1523, but these landings were actually a feint designed to lure the English army to Carlisle.

In fact, Albany planned to cross into England much further east, using a ford across the river Tweed at Wark, near Berwick. Though this ford was guarded by an imposing castle, Albany’s ruse was successful and the castle’s garrison was seriously under strength. Just 300 Englishmen, under Sir William Lyle, faced upwards of 20,000 Scots and French but, from this point, Albany's invasion began to unravel.

Image: the weed covered mound of rubble, which is all that remains of the once mighty Wark Castle.

Having caught the English by surprise, Albany’s men were able to wade across the river and force Wark's defenders to retreat into their castle’s huge octagonal keep. The Scots thought this massive citadel was impregnable but Albany had brought with him one of the largest trains of artillery ever seen in the Borders.

According to the English chronicler, Edward Hall, Albany ordered his guns to blast Wark into submission and the bombardment continued for several days. Eventually, Lyle decided that death was preferable to shameful surrender and he persuaded his men to make one last charge.

“Sirs, for our honour and manhood, let us go forth and fight with the proud Scots and stately Frenchmen, for more shall our honour be to die in battle then to be murdered with guns,” he cried and Hall adds that Lyle's men also chose to die like heroes.

“Then they issued out boldly and shot courageously… and with shooting and fighting they drove their enemies clean out of the place and slew of them, and chiefly of the Frenchmen, 300,” Hall wrote but unlike the doomed Spartans at Thermopylae or Texians at the Alamo, help was on its way.

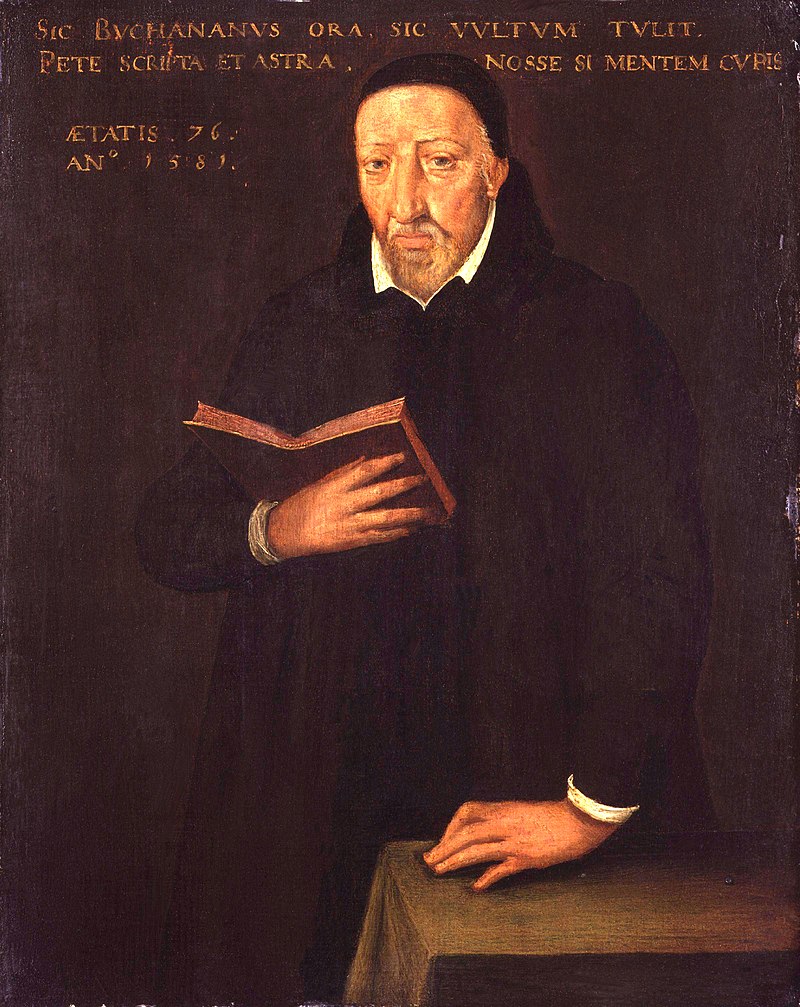

Image: George Buchanan, Scottish historian, scholar and soldier

The Earl of Surrey, who commanded the English army in the Borders, had been warned of Albany’s march east by Isabella Hoppringle, the pro-English abbess of Coldstream, who was a personal friend of Margaret Tudor. Realising he had been outflanked, Surrey hurriedly ordered the men defending Berwick to relieve Wark.

The sudden appearance of English reinforcements persuaded the Scots that another Flodden was imminent, and they fled into the Lauder Hills, but luck was with them. According to the Scottish chronicler, George Buchannan, a sudden snowstorm prevented the Surrey's men from pursing their enemies.

“The same storm caused the English to disband their army, and return home without effecting anything,” he wrote but neither Buchannan, who was present at the siege, nor Hall, who was not, make any mention of Richard de la Pole. So where was the last White Rose?

Image: Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey and (afterwards) Duke of Norfolk

According to Surrey, who sent frequent reports to Henry regarding the progress of his campaign, Richard and Albany had divided their forces whilst still at sea, after which the regent had sailed his fleet of 87 transport ships to the Firth of Clyde and disembarked his forces at Dumbarton.

It seems that Surrey's source for this information was Lord Ogle, a veteran border captain who ran an effective network of spies in the Borders. Yet the equally well informed Lord Dacre, who was the English Warden of the Western Marches, insisted that five more French ships had dropped anchor off Kirkcudbright a few days after the first force had arrived.

Meanwhile, Surrey's own spies told him that Albany had convened councils of war in both Glasgow and Edinburgh. At these councils, the regent had boasted that the English border fortresses would fall as soon as they were attacked and, once the road south was open, the victorious Scots would be joined by Richard de la Pole for a triumphant entry into England.

Image: the French chronicler Martin du Bellay, who met Richard de la Pole on several occasions.

Apart from this brief reference, the English spies make no mention of Richard, which suggest he must have been in Ireland helping Fitzgerald muster his Irish troops. However, a contemporary French source, Martin du Bellay, insists that the White Rose was nowhere near England, Scotland or Ireland.

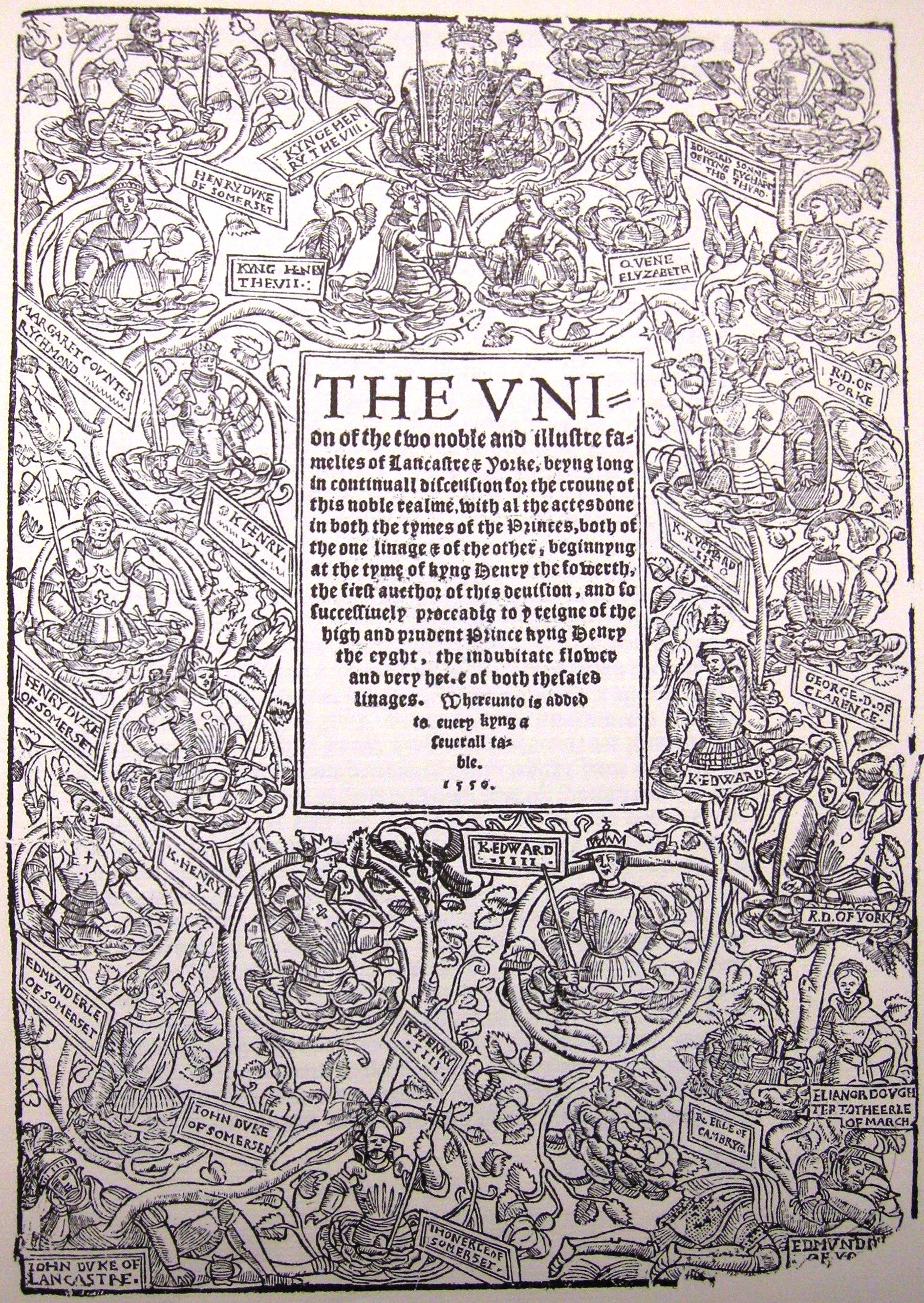

In Bellay's version of events, Richard was with a French army that had left for Milan at the beginning of September, 1523. Yet the French chronicler could have been fooled by the same campaign of misinformation designed to dupe Henry VIII. Moreover, the English chronicler, Edward Hall, states unequivocally that Richard did land with Albany at Kirkcudbright on the 21st of September, 1523.

“The duke of Albany beyng therof aduertised boldly then tooke his shippes and shipped his people, and with lxii saile in sight passed by the West partes of England and coasted Wales, & so with great labor landed at Kyrcowbre in the West parte of Scotland with all his people the xxi day of Septeber whiche wer in nomber iii.M. or there about, and with him was the traytor Richard Delapole.”

Image: the frontispiece of the 1550 edition of Hall's Chronicle, first published posthumously in 1548.

Although Hall was writing several years after the events he describes, he may have had access to sources that are now lost and there is a way to reconcile all these apparently conflicting reports.

Taking all of the above into account, the most likely explanation for Richard’s whereabouts during the 1523 invasion is that he was indeed present during the initial landings in the Solway Firth but he left soon afterwards. In other words, Surrey was correct when he claimed that Albany and Richard had divided their forces whilst still at sea but they had done so after their diversionary force had been landed at Kirkcudbright, not before.

If this theory is correct, the other events described by Surrey, fall into place. Albany would have continued to Glasgow, to raise the Scottish host, whilst Richard would have sailed to Ireland, to collect Fitzgerald’s troops. Furthermore, the failure of Albany's attack on Wark explains how Bellay could maintain that Richard was in command of a French army in theautumn of 1523.

Image: the Solway Firth, was this Richard de la Pole's last glimpse of his homeland?

With his northern border now secure, Henry VIII's army could restart its march on Paris. This prompted Francis to order Richard to return to France immediately and take command of the French forces preparing to defend his capital from the rapacious English.

Given a fast ship and a fair wind Richard could have reached French soil in little more than a week but it was the worsening weather that saved Francis from destruction. The autumn of 1523 was bitterly cold, as well as exceptionally wet, and Henry’s miserable army mutinied long before it reached Paris. Yet this was not the end of the war.

The struggle between Henry, Charles and Bourbon on one side, and Francis, Albany, and Richard on the other, would continue until the fate of all concerned was decided in northern Italy, at the Battle of Pavia. This pivotal engagement, which was fought on the 24th of February 1525, created many of the fault lines that shaped Western Europe for the next three centuries and the part Richard played in the fighting is told in the final chapters of The Last Yorkists.