EDUCATING EDMUND

Oxford, Cambridge and the de la Pole brothers…

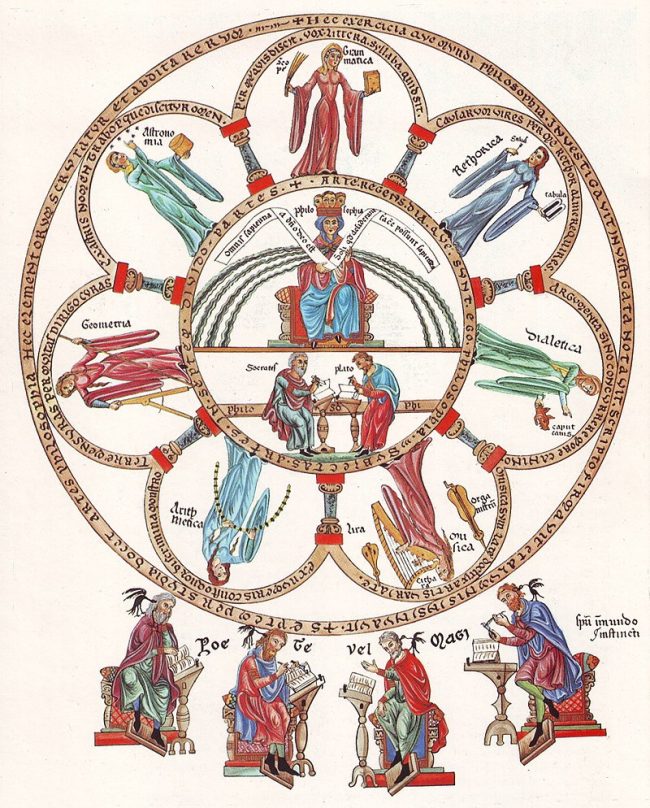

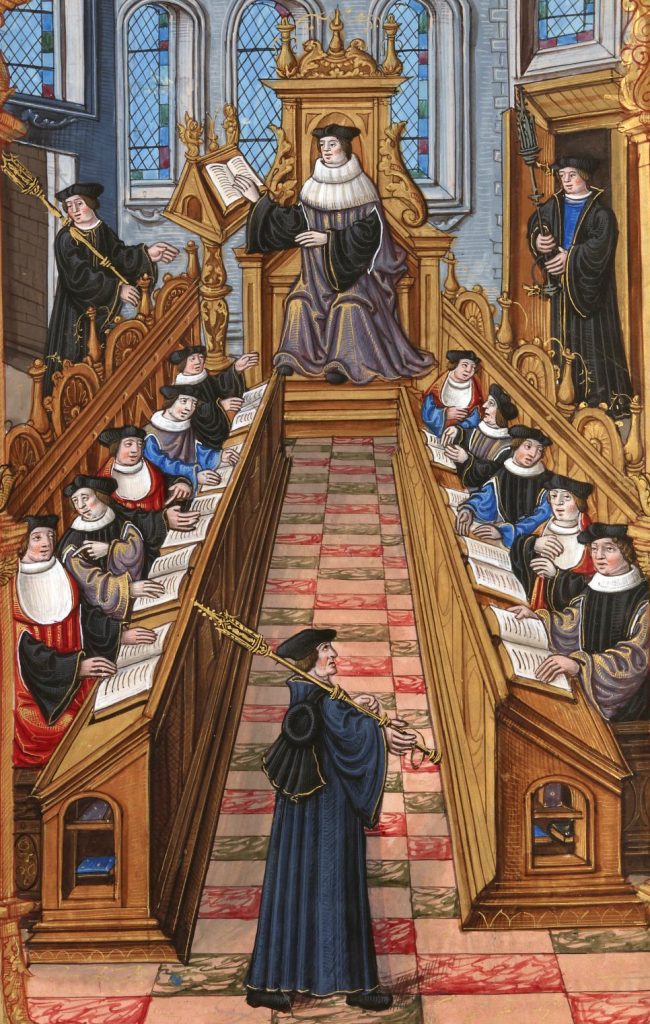

The 15th Century was not kind to England’s universities. The proto-protestant religious movement known as Lollardy, combined with the Western Schism that split the papacy between Avignon and Rome, precipitated a theological and often literal civil war between rival groups of students and dons. To compound the scholars’ misery, the on-going Hundred Years War isolated Oxford and Cambridge from their sister institutions in Europe and then, as now, England’s universities relied on foreign students to underwrite their income and prestige.

These factors notwithstanding, the decline of medieval Oxbridge was accelerated by the propensity of England’s kings and great lords to award lucrative positions in their households to favourites and relatives rather than those with degrees. A lack of graduate jobs therefore meant potential students felt it was not worth the expense and effort of going to university. Last but not least, the value of baccalaureates and doctorates was further diluted by the universities themselves, who repeatedly awarded these degrees to wealthy benefactors who had not studied for them simply to secure their patronage.

The pious Henry VI tried to revive higher education in the mid-1400s by founding All Souls College, Oxford and King’s College, Cambridge. He also established a feeder school for King’s at Eton, near the royal castle of Windsor. Unfortunately for Oxford, England was preparing for the Wars of the Roses and a large section of its student body angered the Lancastrian king by supporting his Yorkist enemies. Henry therefore favoured Cambridge.

Though both universities tried to steer a middle course throughout the three decades of civil strife, Oxford in particular seemed unable to arrest its decline, even after the Yorkist victory gave England a small measure of stability. The university authorities therefore tried to boost their faltering reputation by attracting as a student the nephew of Edward IV.

Oxford’s chancellor at this time was Lionel Woodville, the fourth brother of Elizabeth Woodville and brother-in-law of the king. This close proximity to the throne meant Lionel’s first target was Edward de la Pole the 14 year old son of the duke of Suffolk whose mother, Elizabeth of York, was Edward IV’s sister.

Incidentally Lionel one the first known person to be awarded an honorary degree from Oxford so he was, to a large extent, part of the problem. Perhaps it was to avoid charges of nepotism, which already were being levelled at the Woodvilles, that Lional asked the Bishop of Salisbury, Richard Beauchamp, to approach the king on Oxford’s behalf.

Before becoming a bishop, Beauchamp had been the Archdeacon of Suffolk and the de la Pole boys’ education had been his responsibility. Lionel’s choice of intermediary was, therefore, no accident and he wrote a grovelling letter to ask Beauchamp for his help.

“…your ancient nobility, your supreme integrity of life, and your singular prudence in the conduct of affairs would furnish us with ample material for boasting. Moreover, to these praises of your virtues is added a certain immense authority, by which you seem to excel so far beyond the rest that you can illuminate all of Oxford with a new and unheard-of splendour; for in you lies the greatest privilege of giving us the power to possess and enjoy the most excellent young man, the son of the Duke of Suffolk.” [Anstey, Letter 290, Folio 137a, p453–4]

Heady stuff indeed and there was more to follow:

"You have so thoroughly cultivated his youth with the cradles of virtue and the rudiments of doctrine that he now seems to have grown into a solid man… Believe us, nothing more glorious can happen to your name or to our republic. Which, if at length that most illustrious youth shall be allowed to enjoy, we will bestow upon him the more abundant fruits of morals and science.” [Anstey, Letter 290, Folio 137a, p453–4]

This letter was written early in 1480 but Beauchamp did nothing and Lionel was forced to write directly to the king, his brother-in-law. As befitting what was a fundamentally religious institution the chancellor employed a suitably pious metaphor to strengthen his argument.

“If, as we read, the Caesars reckoned painted statues in the heathen temples a means of securing the worthless glory of this world, how much more glorious will it be for you to have as it were a living likeness of yourself placed here in the capitol of virtue and knowledge, to the honour of the true God.” [Anstey, Letter 291, Folio 137a, p454-455]

This supreme example of the ancient art of royal backside-kissing was also written in 1480 and it seems to have done the trick. The Bishop of Salisbury suddenly promised to bring Edward de la Pole to Oxford in person and the obsequious Lionel wrote to convey his fulsome thanks.

“From the first we have relied wholly upon your influence and aid, and owe you all our thanks for the happy result. In announcing your intention to visit Oxford, and in person lay this noble child in his mother's lap, we see another proof, though we needed it not of your filial affection for us; and we pray that you will soon carry your proposal into effect… and in our temple here take the child in your arms, that we may behold the light prepared for us, to be the glory of our University.” [Anstey, Letter 292, Folio 137a, p456-7]

This letter to Beauchamp is dated the sixteenth day before the Kalends of November (i.e. the 17 October) 1480 but once again the bishop failed to keep his promise. There was still no sign of Edward de la Pole by the following February, so Lionel had to put pen to paper once more.

“We know that you desire our prosperity, but, you can hardly imagine how great has lately been our anxiety. You say, (to quote the words of your elegant epistle) ‘it shall not be long before I come to lay that noble child in his mother's lap;' but we are weary with longing for your arrival, and our old troubles seem to break out afresh. No greater honour could be done for us than to place the King's nephew Edward Pole in our charge, and your own name will at the same time be made immortal…” [Anstey, Letter 296, Folio 138b, p461-2]

The Lord Edward de la Pole did indeed arrive shortly after this letter was sent and there are two more encomiums in the Oxford archive relating to the sons of the duke of Suffolk. However, before discussing these equally sycophantic missives, we need to sound a note of caution because scholars disagree as to which of the king’s nephews was being praised.

The letters from Oxford’s chancellor to the Bishop of Salisbury, and King Edward IV quoted so far are taken from Epistolae Academicae Oxon., published by the Rev. Henry Anstey, in 1898. According to the Rev. Anstey, the nephew of the king mentioned in this second batch of letters, written between 1482 and 1483, is still Edward de la Pole but an earlier work by the Rev. Henry Napier, another clerical antiquary, insists that their subject was Edward de la Pole’s younger brother Edmund.

The de la Poles’ Oxfordshire seat, Ewelme, fell under Napier’s ecclesiastical jurisdiction and in 1858 he published an exhaustive history of his benefice with the rather unwieldly title of Historical Notices of the Parishes of Swyncombe and Ewelme in the County of Oxford. Napier’s work contains both the Latin originals of the de la Pole letters together with his translation and in both cases he insists that the stellar student being referred to was Edmund.

By contrast, Anstey’s book contains only the Latin version of the chancellor’s letters to the king in full but it does include an introductory precis in English. So which is correct? If you would like to compare the two passages that mention Edward/Edmund, here is my translation of the 1482 letter that appears in Anstey:

“Ours is a community, which if it had a thousand voices, could not express how much it owes you. We omit that you sent your nephew, Lord Edward Poole, to your University, as a no mean ornament to it; a young man certainly with a keen, eloquent and splendid mind, so that nature has produced nothing more docile, nothing more acute, nothing more fruitful.”

“Indeed, he listens so well, and he speaks eloquently of what he hears, that he is able to be judged by some divine inspiration. We will never review his splendid nature without seeming to leap and stir at the very thought.” [Anstey, Letter 307, Folio 143b, p478-9]

And here is Napier’s translation of the same letter that appears in his book:

“Our community, if it had a thousand tongues, could not recount how much it is indebted to you. We omit the circumstance, that you have sent the Lord Edmund Pole, your nephew, to your University, to its no slight distinction, a youth, certainly of a penetrating, eloquent, and brilliant genius, so that nature hath produced any more tractable, more acute, more prolific”.

“In such a manner doth he listen to instruction, and so eloquently utters what he hath learned, that it may be regarded as the result of a certain measure of inspiration. Never, in truth, do we reflect on his brilliant nature, without seeming, as it were, to leap with joy and transport at the thought thereof.” [Napier, p162-3 and 168-9]

Moving on to the 1483 letter from the chancellor to the king, here is my translation of the passage in Anstey which refers to Edward/Edmund:

“For it could not have proceeded except from your great affection for us, that you should have caused Lord Edward Poole, your nephew, in whom you saw future examples of probity, to be educated in our gymnasiums; whose virtue is such, and his discipline such, that his virtue can easily be equal to his imperial blood. For when he first moved to your Oxford, he quickly surpassed the others, whom he had chosen as companions in his studies, in those arts with which his age was informed.”

“And he is so modest and gentle towards his own people and all others that there is no one who does not equally admire and praise his constancy and probity; especially when he sees that he excels others in so much nobility, so much glory of genius, so much greatness of excellent merits.” [Anstey, Letter 312, Folio 145e, p484]

And here is Napier’s version:

“For it could not have proceeded from anything, save your great feeling of affection towards us, that you took care for the education at our University of the Lord Edmund Pole, your nephew, in whom you had seen tokens of future worth; whose virtues, in truth, and whose learning is such, as that it may easily vie with his royal descent. For as soon as he had arrived in your Oxford, he quickly surpassed all his fellow students in those sciences, which are taught at his time of life.

Such, too, is his modest bearing and kindness towards his own friends, and all others, that there is no one who does not equally admire and praise his perseverance and virtue, especially when they see, that in proportion as he excels all others in nobility, so he also does in the fame of his talents, and so, in short, in the greatness of his extraordinary merits.” [Napier, p163-4 and 169]

Adding weight to Anstey’s belief that all the letters were written about Edward is the fact that the older de la Pole entered the church before he went to Oxford and this may explain the delay in his arrival. Specifically, Edward was admitted to the Archdeaconry of Yorkshire in 1480 and appointed Archdeacon of Richmond in January 1484. As degree courses lasted around four years, Edward’s time at Oxford fits perfectly with his clerical appointments.

On the other hand, it appears that Edward IV sent Edmund to Oxford in 1481 to hear the aforementioned lecture on theology, which the king had funded, and it is not beyond the realms of possibility that the younger de la Pole stayed on as a student. If this theory is correct then there is the possibility that the 1483 letter at least refers to Edmund.

A further clue is contained in the way both versions of the 1482 and 1483 letters stress that it was the king’s idea to send Edward/Edmund to Oxford. As we have seen the earlier letters make it clear it was the university authorities who first had the idea of acquiring Edward de la Pole as a student, not the king’s, and they needed the Bishop of Salisbury’s help to achieve this goal. Of course, the later letters could simply be further examples of the egregious flattery to which the university’s chancellor, Lionel Woodville, was prone.

If Edmund did attend Oxford, it seems that his academic career was cut short by the death of Edward IV in April 1483. Edmund is recorded as being made a Knight of the Bath by Richard III as part of his coronation celebrations, whilst his brother was appointed Archdeacon of Richmond the following year. In each case it is likely that Richard III made these appointments in order to strengthen his grip on power both north and south of the Humber.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Napier’s belief that it was Edmund who is the subject of the later letters was endorsed by several eminent 19th Century experts in early Tudor history including James Gairdner. It was Gairdner who catalogued Henry VII’s letters and state papers and he also wrote the entry for Edmund de la Pole in the original Dictionary of National Biography, published in 1885, which reads as follows:

POLE, EDMUND de la, Earl of Suffolk (1472?–1513), was the second [sic] son of John de la Pole, second duke of Suffolk [q. v.], by his wife Elizabeth, sister of Edward IV. About 1481 Edward sent him to Oxford, mainly to hear a divinity lecture he had lately founded. The university wrote two fulsome letters to the king, thanking him for the favour he had done them in sending thither a lad whose precocity, they declared, seemed to have something of inspiration in it. [DNB, 1885-1900, Volume 46]

Though Gairdner does make mistakes, for example Edmund was the duke’s fourth son not his second, it is entirely possible that Edward and Edmund attended the university at the same time. Edward would have been about 14 in 1481, when the Bishop of Salisbury eventually brought him to Oxford, and as we have no record of Edmund’s exact date of birth, he could have been of a similar age in 1483, when the second letter in question was written.

Though 14 was the theoretical minimum age to begin a degree course, we have already seen how university authorities were happy to bend the rules in order to secure a wealthy patron. Furthermore, Edward and Edmund were not the only de la Poles to frequent the olive groves of Academe. Their younger brother, Humphrey, took bachelor degrees in both civil and canon law, as well a doctorate in the latter, but he did so at Cambridge rather than Oxford.

The East Anglian university’s register contains the following entry:

POLE or DE LA POLE, HUMPHREY. Pensioner, at Gonville Hall, 1490-1505. 3rd [sic] son of John, Duke of Suffolk. B.Civ.L. and B.Can.L. 1496-7; D.Can.L. 1500-1. Ordained acolyte (Ely) Sept. 24, 1491. Prebend of St Paul's, 1494-1509. Rector of Leverington, Cambridgeshire, 1500. Rector of Hingham, Norfolk, until 1513. Died 1513. [Alumni Cantabrigienses. vol.1 part 3 p.378]

Incidentally a pensioner at this time was someone who paid board and lodging to the residential hall of a college, not someone in receipt of a retirement income, and Humphrey was the duke’s fifth son not his third. It is also interesting that the Cambridge register of students mentions two more de la Pole brothers, Geoffrey and William, but with the caveat that their entries may have been confused with that of Humphrey’s.

POLE, GEOFFREY DE LA. Pensioner, at Gonville Hall, 1499. Son of John, Duke of Suffolk. Donor of manuscripts to the library. Probably buried at Babraham, Cambridgeshire. Some doubt exists as to the identity of this Geoffrey. Possibly a mistake for Humphrey (1490), as [is] also the Grace, 1494, to admit to congregations 'William de la Pole, son of the Duke of Suffolk' as neither of these names occurs in the pedigrees. [Alumni Cantabrigienses. vol.1 part 3 p.378]

The reason for the switch of de la Pole allegiance from Oxford to Cambridge may be entirely due to the Battle of Bosworth. It hardly needs to be said that this battle marked the end of the House of York and the beginning of the House of Tudor, or that the new king, Henry VII, believed himself to be the true heir of the last of Lancastrian monarch, Henry VI.

As mentioned earlier, Henry VI had been more enamoured with Cambridge than Oxford and it was his Tudor successors, Henry VII and Henry VIII who completed his masterpiece of King’s College. Considering that anyone with Yorkist blood was treated with deep suspicion by the Tudors, it is likely that Humphrey hoped to keep his head by spending his days as a country parson.

To be sure, Humphrey’s quiet clerical life is in stark contrast to careers of his brothers. Both Edmund and Richard de la Pole spent their adulthood as desperate exiles mired in the snake pit of European politics and their story is told in The Last Yorkists.